"Never again is now": When remembering becomes a political act

"Those promises we made that we would not let it happen again, that we would be the friends that we wish we had in ’42 — that bill is due.” - Seattle resident Stanley Shikuma

“We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late. Procrastination is still the thief of time. Life often leaves us standing bare, naked and dejected with a lost opportunity. … There is an invisible book of life that faithfully records our vigilance or our neglect. … We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent coannihilation.” - Martin Luther King Jr., 1967

Two recent episodes in Seattle highlight our nation’s current challenges with remembering the past, and remind us that remembering can be a political act.

In January, someone defaced the Japanese American murals in Nihonmachi Alley, in Seattle’s International District. The series of public art murals commissioned by the Wing Luke Museum in 2019 highlight major landmarks of Seattle’s original Japan Town and commemorate the history of Japanese American exclusion during World War II. The vandal covered all of the faces and images in the murals with black paint.

In February, the Pike Place Market Foundation abruptly canceled a Day of Remembrance gathering to mark the anniversary of Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. The order, issued soon after the United States entered World War II, authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed to be a threat to national security. EO 9066 was used to incarcerate 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living within 200 miles of the West Coast, many of whom were United States citizens, in ten concentration camps scattered across the country for the duration of the war.

These two acts, one individual and one organizational, one aggressive and criminal and the other administrative and institutional, were targeting a particular population that has been historically othered in our nation’s history. One hateful and racist act of vandalism, and one cautious and fearful act of denial. Both are representative of a larger movement to rewrite a history of injustice. Each forms part of a pattern of outcomes taking place across the nation as a result of a series of new presidential executive orders that are simultaneously seeking to exploit EO 9066 and to erase the memory of its unconstitutional actions.

Both episodes represent conditions of the growing trend of anticipatory obedience taking place amid the massive, chaotic flood of downright meanness from the second Trump administration: a dangerous trend that emerges within societies in times of oppression and fear, caused by a rise of authoritarian power that intentionally fuels an “us vs. them” paradigm, directed at the enemy within. We in America need only look back to Jim Crow laws in the South, Native American boarding schools, Japanese American exclusion during World War II, and McCarthyism and the communist scare of the 1950s.

Defacement of Japanese American Mural in Nihonmachi Alley

The defacing of the Japanese American mural can be tied to a larger effort to reject and deny diversity. The act of erasing the past through defacing a memorial is a more violent version of efforts around the country to remove historical references to women, people of color, and indigenous peoples from our curriculum and cultural interpretation. The act of defacing the Japanese American mural is nothing new. The rise of anti-Asian hate crimes started during the first Trump administration.

The act of defacing is an act of stealing someone’s identity.

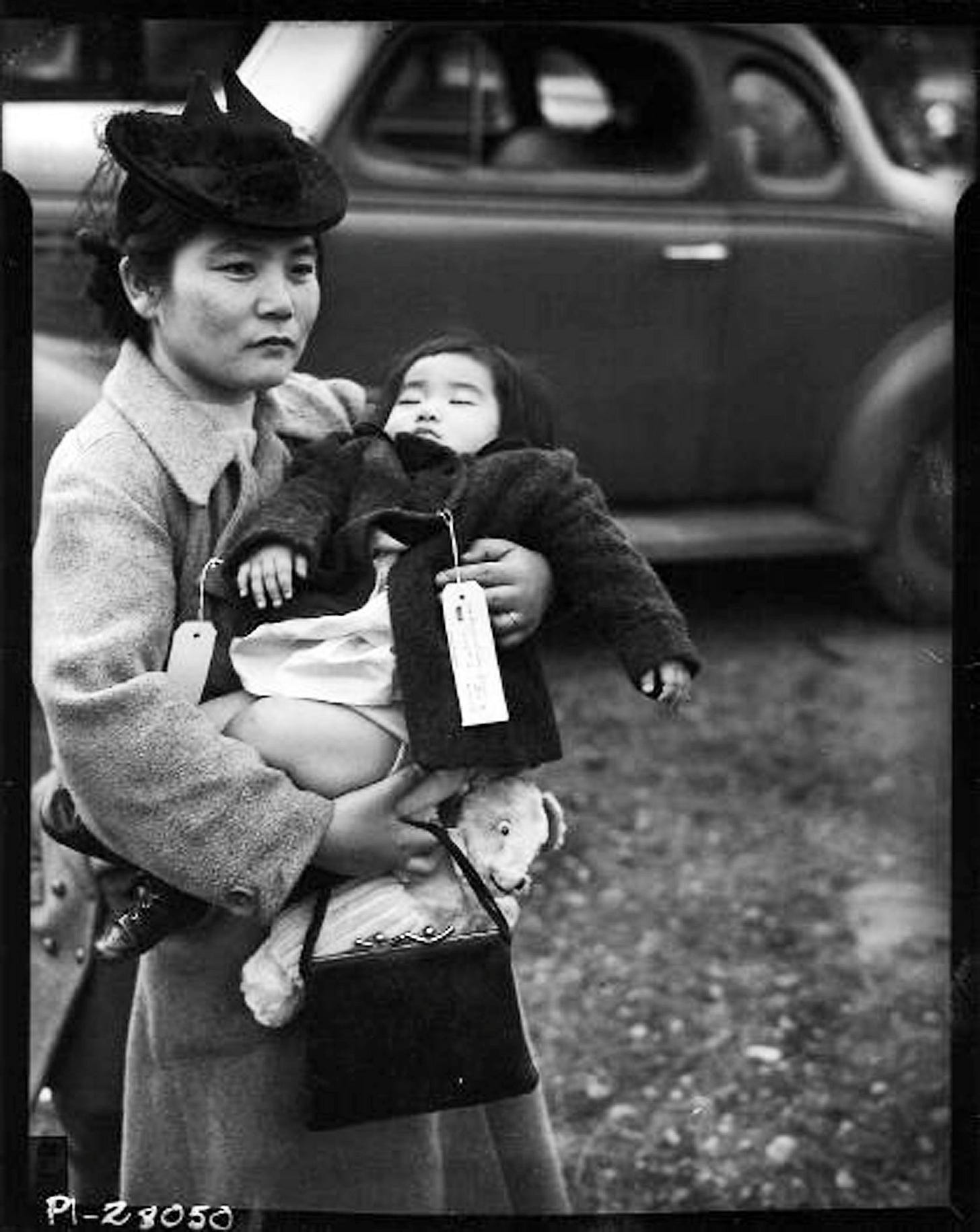

They are real people with real stories. Two of the people featured in the defaced Japanese American mural are Fumiko Hayashida and her infant daughter Natalie. Their photograph is one of the most widely used images and symbols associated with Japanese American exclusion. It was taken at the former Eagledale Dock on Bainbridge Island, Washington on the morning of March 30, 1942, as they were being forcibly removed from their home by the United States Army, into exile and incarceration as part of Executive Order 9066. Fumiko, age 31 in 1942, and Natalie, thirteen months, were both born on Bainbridge Island and were United States citizens at the time, as were most of the 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who were rounded up during this period of Japanese American exclusion.

By 1941, three generations of Hayashidas were living and farming on Bainbridge Island. They owned and leased enough farmland to make their family one of the largest local producers of the famous Marshall strawberry, which at that time was considered one of the finest-tasting strawberries in America.

Most Japanese residents of Bainbridge Island would make special trips to Seattle to shop at the original Higo Store, a Japanese-owned mercantile, at the corner of Nihonmachi Alley, that served the community for decades and is now operated by the artisan gallery KOBO.

The Hayashidas were members of the Winslow Berry Growers Association, a collective that from 1912 to 1942 represented more than seventy Island Japanese berry farmers and made Bainbridge the strawberry capital of the Pacific Northwest. They had become a formidable economic force and foundation for the booming strawberry industry centered around Puget Sound that involved producers, processors, distributors, wholesale and retail sellers, and restaurants regionally and globally. In late spring and early summer of 1941, these Bainbridge Island farmers, on just over seven hundred acres, harvested a record 3.5 million pounds of strawberries. They were anticipating an even greater harvest the following year.

The success these early Japanese immigrants experienced in America was accomplished within the racist context and legal landscape of federal and state Alien Land Acts, which prevented any Asian immigrant from owning land, voting, or becoming a citizen.

After the United States entered World War II and President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, the agricultural prospects of the Hayashidas and their fellow Japanese berry farmers had quickly diminished, as they were forced from their farms and incarcerated months before they could reap the benefits of their harvest.

The Japanese residents of Bainbridge Island were the first community forcibly removed under EO 9066. On March 24, 1942, a notice was posted by the United States Army giving these residents and citizens only six days to settle up their affairs for their farms, homes, and lives and pack only what they could carry to a destination unknown and for an indefinite period of time. With two infants to care for, Fumiko Hayashida filled her suitcase mostly with cloth diapers.

The removal of the Japanese population from the Pacific Northwest was done not only for strategic military advantage, but also for economic advantage. The fact that they were so dominant as an economic and industrious force in the early decades of the twentieth century also added to the inherent prejudice ag

0ainst them. Denying their freedom and exiling these farmers, market sellers, and community businesses from their livelihoods completely stripped them of the economic leverage they had worked decades to achieve. After the war, having either to reclaim their former lives or to start anew, few would ever be able to reproduce their pre-wartime economic success.

Six decades later, when Fumiko Hayashida was among the eldest Bainbridge Island survivors of Japanese American exclusion, she became the voice for a movement to build a memorial at the site where her iconic photo was taken. She was invited to the United States Congress by then-Representative Jay Inslee, to testify in favor of making this Japanese American Exclusion Memorial a federally recognized site. On March 30, 2009, 98-year-old Fumiko Hayashida got onto the cab of a construction backhoe and broke ground for the long-awaited “Story Wall” for the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Memorial (BIJAM), now open to the public and operated in partnership with the National Park Service.

Both Fumiko and Natalie are people I have known and worked with in my professional and community life. Fumiko passed away in 2014. Natalie now lives with her family in Texas.

In 2011, when Fumiko Hayashida was 100 years old, she and Natalie joined a delegation from Bainbridge Island to the former Manzanar concentration camp in Independence, California. I had the honor to organize and facilitate the delegation to bear witness to the makeshift, one-square-mile War Relocation Center to which the U.S. military exiled them and 10,000 others during the war. It’s now an historic site operated by the National Park Service. Sixty-nine years later, soon after returning to Manzanar, Fumiko said, “This was our home. ... It was a long time ago. ... And, I came home. I remember.”

Denial of Day of Remembrance

Pike Place Market, one of Seattle’s most famous tourist attractions, is historically intertwined with Seattle’s Japanese immigrant experience. In the decades after it opened in 1907, more than 75 percent of the Market stalls were supported and occupied by Japanese farming, food, and flower businesses. Japanese American vendors were considered the backbone of the Market’s success prior to World War II. Executive Order 9066 forced all Japanese vendors from their Market stalls, cutting off their businesses and livelihoods. Pike Place Market barely survived during the war, and it has never fully recovered those market stalls in the eight decades that followed.

In February 2022, for the 80th anniversary of Japanese American exclusion, Pike Place Market dedicated a cherry blossom tree and a commemorative plaque to the Japanese American community for their historic contributions, and held its own Day of Remembrance. At the time, they stated:

Before the 1942 Executive Order, over 75% of Pike Place Market farmers were Japanese. These family farmers were forced off their land, out of our city, and never returned to sell at Pike Place. It is with sincere regret that the Market didn’t do more to keep these farmers safe in their community.

In denying the application for this year’s Day of Remembrance event, with the theme of “Stop Repeating History”, organized by Tsuru for Solidarity – connecting the Trump Administration’s current treatment of immigrants to the experience of Japanese American exclusion – the Pike Place Market Foundation claimed that the event’s messaging did not align with its values.

Isn’t standing up to injustice a vital part of remembrance? Tsuru stated: “Our stance is that you can’t have remembrance without resistance. They go hand in hand.” A few days later, Pike Place Market walked back its original statement and apologized for canceling the event. Tsuru held the February 19 event in the International District instead.

What would make a Day of Remembrance in 2025 any different from other years? Pike Place Market’s initial action of denial is part of a bigger national wave of staffing dismissals, program cancelations, curriculum censorship, funding cuts, and removal of plaques, displays, and exhibits representing diversity, equity, and inclusion. What kind of fear would lead our cultural, academic, and governmental institutions to be afraid to remember, to condemn exclusion, and to call out historic as well as contemporary injustices?

The legal justification for Executive Order 9066 in 1942 was the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, the same eighteenth-century law being used today by President Trump to justify rounding up and deporting immigrants. EO 9066 was also used to detain and incarcerate U.S. citizens. The Supreme Court later found that to be unconstitutional, and Presidents Reagan and Bush took part in making apologies and reparations.

The behavior of the Pike Place Market Foundation is an instance of what social scientists call anticipatory obedience. We have troves of global lessons from previous and current dictatorial regimes about the societal consequences of this modus operandi. It never ends well for the compliant and obedient trying to save their own skin.

The history of the last century has given clear road maps for how the subtler and more minor conditions of anticipatory obedience expand what society will tolerate in treatment of the other in times when fear rules, creating a slippery slope that eventually sets the stage for major dictatorial behavior, human rights violations, crimes against humanity, and even genocide. Read The Sunflower by Simon Wiesenthal, about the rise of antisemitic conditions in his Polish town during the 1930s, which made it so easy for the eventual Nazi occupation to perpetrate the genocide upon the Jews with compliance and little resistance from the rest of the population.

What does it say that eight decades later, the hate and racism are still present, the othering continues, perceived enemies of the state are being rounded up? Is this a failure of education? Is it human nature to have such a short-term collective memory? Is real democracy such hard work?

What does it say when the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the “greatest generation,” who fought and died during World War II to rid the world of the authoritarian and fascist values and practices of Nazism, begin to believe in and advocate for those same values and practices in our country eight decades later?

Where do we go from here?

Every March 30, the Bainbridge Island Japanese Community and Exclusion Memorial hosts a Day of Remembrance ceremony marking the day, hour, and minute in 1942 when 227 Japanese residents of Bainbridge Island began their walk along the Eagledale Dock to board a special ferry, accompanied by the U.S. Army, for a two-day journey into exile at the Manzanar concentration camp in the high Sierra desert of California. They were the first community to be forcibly removed from their homes, farms, and livelihoods under Executive Order 9066.

While there have been attempts over the decades to challenge the federal recognition of this memorial and question the unconstitutionality and injustice of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, this ceremony has been completely nonnegotiable to the Bainbridge Island community, which now sees this Japanese American story as its own story.

Dr. Frank Kitamoto was Bainbridge Island’s equivalent of Martin Luther King, Jr. After four decades of relative public and familial silence about their exclusion experiences, Frank, an Island dentist who was 2 1/2 years old when his family was exiled to Manzanar, was a catalyst for persuading his own Japanese American community to share their oral histories and commemorate their stories, in an exhibit that opened during the period of United States government redress for Japanese Americans who endured incarceration during World War II. Frank was also the driving force behind the creation of the Japanese Exclusion Memorial on Bainbridge Island. He was a mentor to me and many others who came into his orbit, and he co-led our Bainbridge Island delegations to Manzanar until his passing in 2014.

Frank Kitamoto engaged tens of thousands of people in his capacity as President of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community (BIJAC). He talked about love being the antidote to fear, and about forces of authentic and inauthentic power that can both shape and repel the instinct to other and to deny citizens their civil and human rights. He also spoke about the place of tombo, Japanese for courage, in our lives, especially during trying times. “Courage is not being fearless,” he said, “but being able to overcome fear, to focus away from myself to free me to help another. That’s what heroes do. Their souls override their fears for themselves so they can risk for another.”

Resisting anticipatory obedience is the call for this moment. Today, maybe more than ever, remembering has become a political act. In a piece about the fear that was on display in the Pike Place Market Foundation’s cancellation of the Day of Remembrance, Seattle Times columnist Naomi Ishisaka quotes Stanley Shikuma, a member of Tsuru: “It’s a moral imperative. Never again is now, and those promises we made that we would not let it happen again, that we would be the friends that we wish we had in ’42 — that bill is due.”

Jonathan Garfunkel is working on two projects with Blue Ear Books chronicling the Japanese American experience on Bainbridge Island, Washington. One is the story of the Island’s last Japanese American farmer, Akio Suyematsu, his family, and their historic farm. The other examines the impact of Executive Order 9066 and Japanese American exclusion on the Bainbridge Island community.

So very grateful you appeared on my Substack feed. This is an amazing essay. I am so deeply moved… thank you for using your voice to speak against the erasure that is threatening our country, our humanity. I need to sit with this a while and listen to my heart and what is resonating within it that has been set into motion by you. Thank you. 🙏