It is worth reflecting at this moment on where our country stands and what may lie ahead. Several factors should give us pause. Not the least is that, for the first time ever, a convicted felon is about to ascend to the highest office in the country, having been duly elected by a slight plurality of citizens who bothered to vote.

The November 2024 election took place under unique circumstances. Most Americans felt we were headed in the wrong direction under Joe Biden. His anointed successor Kamala Harris could not think of anything she would do differently than her very unpopular boss. The only options then for many were to vote for Harris’s opponent or not to vote at all.

It was clear the country needed new leadership, but what does good leadership even mean? Political leaders worldwide are suffering from a lack of trust, or at least a serious lack of enthusiasm. By his own commitment, Biden was supposed to be a transitional president, to have groomed the next generation of Democrats, yet he chose to run for reelection. He presided over an economy that wasn’t working for too many working-class Americans, and his support for the genocidal campaign in Gaza had turned off too many.

In addition, spending tens of billions supporting the Gaza assault and the war in Ukraine while too many Americans were struggling financially struck a death knell for Biden’s campaign. His declining health and refusal to reconsider his candidacy until it was too late led to the electoral disaster faced by the Democratic Party and the country. This will likely ensure that he will go down as a terrible leader, if not one of the worst presidents of our lifetime.

That brings us to the question of what can or should be reasonably expected of a good leader. At this time in American history, it is worth looking at Andrew Russell’s book The Leadership We Need: Lessons for Today from Nelson Mandela. Through 27 ½ years of incarceration, Mandela stayed steadfast to the vision of an apartheid-free South Africa, and in the process helped his country transition to a true democracy and avoid the bloodbath that many believed was inevitable.

Throughout his long imprisonment Mandela refused to take the easy way out, several times declining the possibility of becoming a free man, but on terms that violated his core principles. Also noteworthy was his empathy for all around him, including fellow prisoners and even his jailers. Mandela had a distinctive ability to look at the circumstances through the eyes of his adversaries. Somehow, he managed to see the situation through the eyes of those who were committing grave injustices against the people for whom he cared deeply.

Upon becoming the first elected president of a free South Africa, Nelson Mandela set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission that helped the nation to heal.

My wife and I had the pleasure of hosting Andrew Russell at our home in Maryland last October. Through our many casual and formal conversations, I was able to learn more about apartheid South Africa and about how Andrew himself, a white South African born in 1964 and growing up in Cape Town, had been largely shielded from knowledge of the apartheid system that was all around him. It was interesting to note how much antidemocratic governments are able to control the narrative for vast numbers of their citizens, even in a democracy.

(The situation in Israel is a current example of how large segments of a population can be made oblivious to the death and destruction their government is unleashing within a few miles of their own daily lives.)

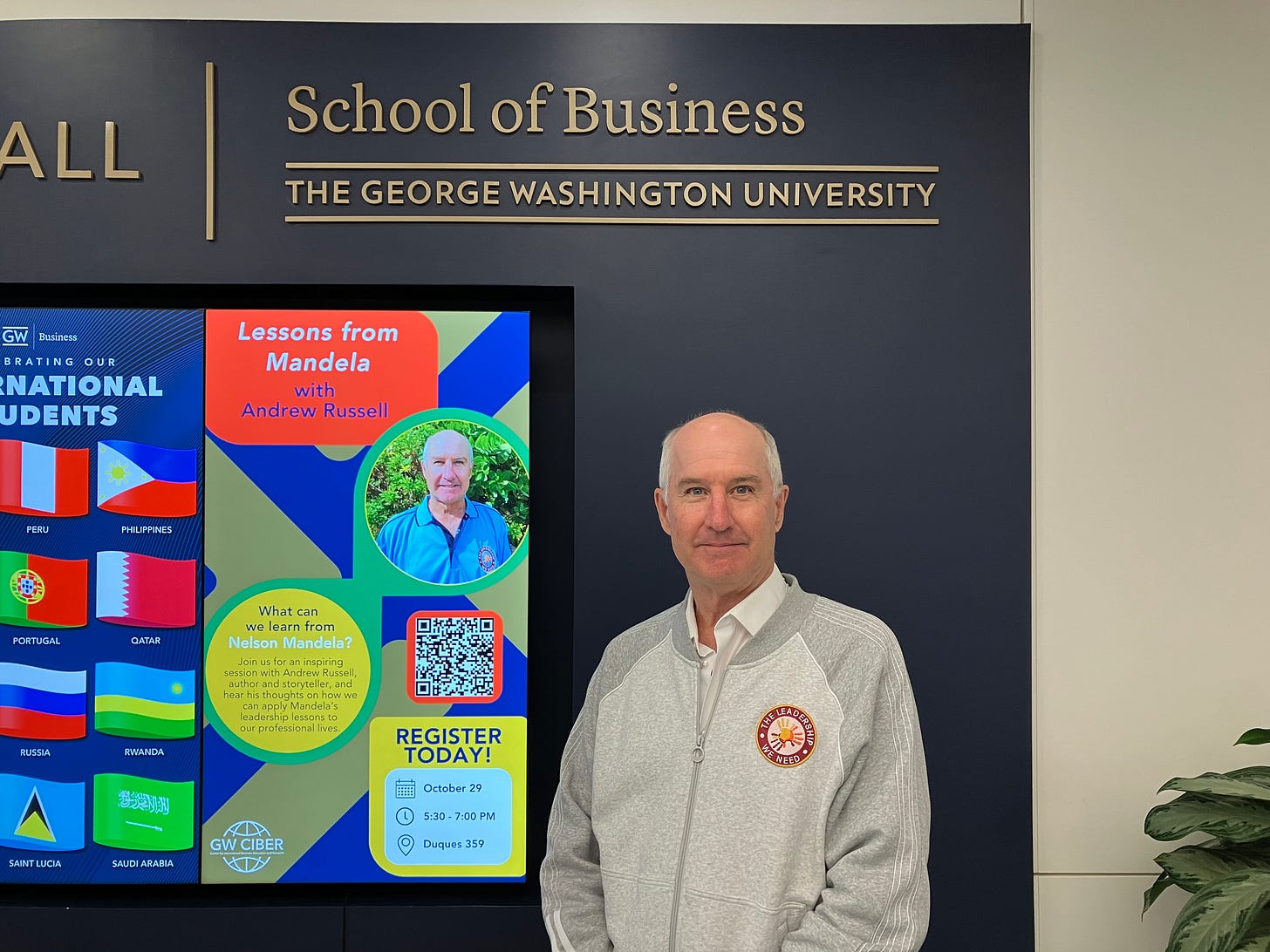

It is also hopeful to hear the story of Andrew Russell for other reasons: How, once he became aware of the real injustices in the South African system, he was quickly able to stand for what is right. In the several gatherings we held with Andrew at my home and at George Washington University in Washington, DC, we could see the yearning among the attendees for better leadership, and a desire to learn from the example of Mandela and South Africa.

Andrew’s visit took place a couple of weeks before the November 5 election, but there was a deep sense that, regardless of the election result, this country would remain seriously off track and lacking the leadership it needs and deserves.

As the new regime takes over in the U.S., the quest for better leadership continues. The U.S. electoral process has been so completely taken over by deep-pocketed special interest groups that it is hard to see how and when a real democratic process of choosing leaders can emerge anytime soon. While the example of Mandela and South Africa gives one hope, still it takes a leap of faith to see how such learnings can actually be implemented in the oldest democracy in the world.

S. Qaisar Shareef is the author of When Tribesmen Came Calling: Building an Enduring American Business in Pakistan, published by Blue Ear Books.