The price of moral courage

In South Africa authoritarianism did not happen overnight but by degrees, ever ratcheting up the power of the state to control speech and deprive liberty.

In the 1980s, when I was an idealistic young college student, I joined the campus protests against apartheid in South Africa. We thought we could coerce institutions into divesting from the country with our very bodies. If everyone pulled their money out of the country, the idea went, the regime would capitulate. So we dutifully lay down en masse in front of banks to thwart commerce, and occupied the state capitol in Madison, Wisconsin. I learned that sleeping on a marble floor is miserable. I don’t recall if we actually prompted any divestment.

I knew the name Nelson Mandela, largely from the infectiously upbeat song “Free Nelson Mandela” by the British group The Specials, which came out in 1984 and was played a lot on the student union jukebox. It seemed a righteous cause, protesting apartheid, and the soaring chorus in the song was like a divine affirmation of that. It was all very easy, and simple, and entirely pain free.

It’s hard for me to look back on my deeply naïve formative years. That is to say, I’m glad to realize that protesting apartheid was the right thing to do, but I knew nothing about life in South Africa. I had no clue what it meant to be black in America, much less in South Africa. I did not know what an authoritarian regime will do to its own citizens. Many years later I saw a haunting photo of the body of Steve Biko, beaten to death by the regime’s security police, and I started to understand.

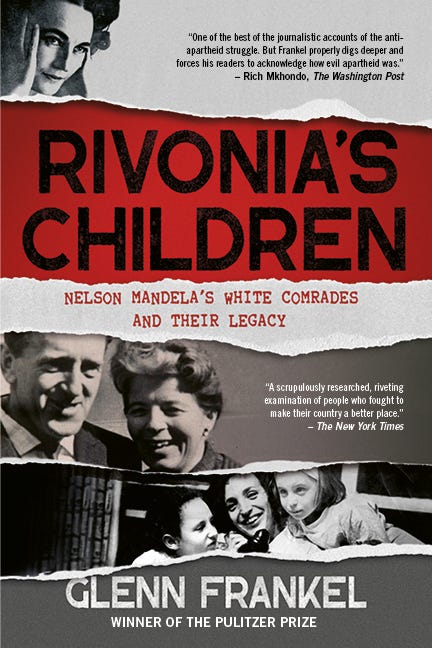

Still, I was unprepared for my reaction to Rivonia’s Children: Nelson Mandela’s White Comrades and Their Legacy, a devastating account of South Africa by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Frankel, first published in 1999 and now reissued by Blue Ear Books. It’s the story of white South Africans who tried to turn the tide against apartheid twenty years before the song “Free Nelson Mandela.” It’s the story of a country sliding into darkness, the tragic corruption of the law, the complicity of the lawmakers, the barbarism of a police state. But at its heart it’s a study of astonishing conviction, courage, and sacrifice to turn a society away from its appalling injustice.

In the foreword to the new edition, Frankel tells the story of Ruth First. Like many other of the white South Africans actively opposing apartheid, First is Jewish and a communist. She had fled the country years before when, in 1982, she received a package in her new home in Mozambique. “The package exploded,” Frankel explains, “blowing Ruth out of her shoes and spraying blood and flesh all over her office wall.”

It is among the many vicious actions by the South African police state to stamp out dissent over more than three decades: the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, the banning of political parties and opposition publications, the endless incarceration of black and Indian activists, wiretapping phones and tailing cars, and – the central story of Frankel’s book – the imprisonment and trial of Ruth First’s comrades after the police raid on Rivonia, the headquarters of their organizing work.

The police raid takes place on July 11, 1963. Members of South Africa’s Special Branch police, driving incognito in a white laundry van and guided by a disgruntled tipster, barge into a suburban home surrounded by tall trees. A dozen officers arrest Rusty Bernstein, Bob Hepple, Walter Sisulu, Denis Goldberg, and several others. They find political treatises, maps, letters, lists of names, and documents on the Umkhonto we Sizwe sabotage campaign. Hendrik van den Bergh, the new commander of the Special Branch, is “amazed by the amateurishness of the conspirators in collecting and preserving such a trove of incriminating evidence.” The police do not find handguns, rifles, or bombs – only papers. “Revolutionaries they might have been, but the men of Rivonia … offered no resistance. In the end, they delivered not only themselves but enough documentation to destroy their own networks and convict themselves of high treason, sabotage or any of a dozen other offenses in the state’s long and growing list of political crimes.”

There is a deep sadness to the machinations of the state over the months that ensue. These revolutionaries are lawyers and architects, communist ideologues, and family people with children. They do not flee into the woods with armed militants, but instead wait in their offices and suburban homes for the authorities to come for them. The state has given the security apparatus everything it wants to crush dissent: bugging homes, house arrests, banning membership in organizations, criminalizing individuals to be with other individuals. The backdrop is the prisons and the legal prerogative of the state to imprison anyone for ninety days for any reason. The interrogators know their craft. Black and Indian prisoners are tortured. The white prisoners are held for months in solitary confinement to induce confessions and ratting out of their comrades. Deprived of visitors, even family members, deprived of decent food and even of reading material, the Rivonia men and women psychologically unravel in the ghastly isolation. It is excruciating to witness, a wonder that they somehow survived.

I had nightmares for several nights as I read Rivonia’s Children. The dreams were surreal scenes that I interpreted as metaphors of a police state. They seemed clearly a reaction to the anguish of Ruth First, Rusty and Hilda Bernstein, Harold Wolpe, and others who were so helpless before the apparatus of the South African police state and who suffered so grievously. But perhaps my subconscious is also worried too that authoritarianism is far from dead and buried. In South Africa it did not happen overnight but by degrees, ever ratcheting up the power of the state to control speech and deprive liberty.

The incoming American president vows to round up millions of illegal immigrants and put them in camps. Do you think that’s an empty promise? Do you think that’s going to happen without creating our own version of a police state in the 21st century? Will we witness citizens with the same moral courage as Ruth First, Rusty and Hilda Bernstein, Bram Fischer, Harold Wolpe, Joel Joffe, Joe Slovo, and others, willing to pay the price to defend decency, humanity, and the law?

“They had taken a risk that others of their background and social status would not take, had eschewed comfort and thrown away security, when others chose to go along and reap the benefits of silence and compliance,” writes Frankel in the epilogue to his affecting and superbly reported book. Americans may be similarly tested in the years to come.

Jeb Wyman is the author of What They Signed Up For, a book of 18 oral histories of American veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, to be republished in a second edition in 2025.

Wyman's post is an excellent read, a reminder and review of angreat book about the struggle against apartheid. a struggle that was not only waged by the black majority, but brave and courageous white folks too. This review takes us back, through Frankel's book to those times.