Why publish books? Two cases in point

Sometimes documentation is what is called for, first and foremost.

Dear friends,

A cherished totem from my earlier career as a journalist covering Southeast Asia is Jakarta Crackdown, a book published in Indonesia in 1997 - during what turned out to be the last days of the Suharto dictatorship - by three civil society groups: the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI), the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA), and the Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information (ISAI).

The book was published in both Indonesian and English and distributed independently (more on which, see below). The Suharto dictatorship had been in power at that point for three decades and finally fell in 1998. The tone of the back cover text is earnest:

The riots that rocked Jakarta on 27 July 1996, and the political events preceeding [sic] and after that date, have left deep wounds in Indonesian society. An instance of violence whose existence in our history was never sought. It is an important moment in the path stubbornly being taken by the New Order Government. The Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI) is being torn to shreds. A number of young people have paid dearly for things they did not do. They, activists in the People’s Democratic Party (PRD), are accused of manipulating political events, and have been chased after, arrested, detained and accused of subversion. Non-governmental organizations have been targeted, and a labour leader is on trial. The 27 July Incident has been used as a trigger to prompt a crack down [sic] on pro-democracy activists.

“The government has become increasingly inclined to use physical violence in dealing with movements for change in society,” says Arbi Sanit, a senior lecturer at the University of Indonesia, in the Foreword to this book. The government blames communism as being behind it all. But an opinion poll conducted among the urban middle class concludes that it is the government itself that is the cause, that it is the government who is behind the coup d’e’tat [sic] against PDI leader Megawati Soekarnoputri. Many were angered at the forcible seizure of the PDI headquarters. That anger proved uncontrollable, igniting the riots. Buildings were set ablaze, innocent victims fell.

Jakarta Crackdown is a hastily-compiled collection of interviews and documents about the events of July 1996, and its main purpose was nothing more glamorous than documentation. Sometimes documentation is what is called for, first and foremost. And what I’ve always remembered as the book’s most revealing and instructive aspect is this: that Indonesian law during the Suharto era required pre-censorship of periodicals, but not of books. If you were publishing a magazine, you had to submit each issue to state censors before publication. If you were publishing a book … well, you could go ahead and publish your book, submit one copy to the state censors, and then wait for them to get around to banning it. And meanwhile you could print thousands of copies and distribute them all around Indonesia.

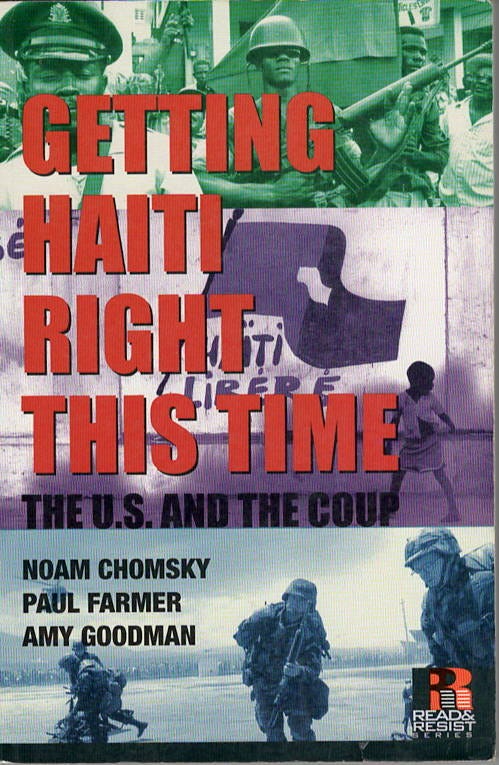

Another of the goodies on my bookshelf is Getting Haiti Right This Time, a similar collection published in the U.S. in 2004, the year of the second coup against democratically elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Twenty long years later the fact that that coup was a coup, and a U.S.-sponsored one at that, is largely uncontroversial. At the time, the Bush administration was taking great pains to claim that it was nothing of the sort (notwithstanding then-VP Dick Cheney’s ever-so-quotable quote: “We’re glad to see him go”). I had the opportunity, in a fortuitous one-on-one conversation in a restaurant booth in Washington, DC, to congratulate one of the book’s co-editors, Amy Goodman. “It’s a great book,” I told her. She demurred, noting with chagrin that it contained many typos. I laughed because, in such a case, who cares about typos? The point was to get such a book in print and in circulation, quickly, in the hope of influencing public awareness and maybe even decision-making, but at least achieving the equally important goal of merely documenting factual and historical truth.

Both of these books have been on my mind over the past, oh, ten days or so.

Another really good book is Lustrum, Robert Harris’s historical novel of Rome, narrated by Cicero’s slave Tiro, who observes: “There are no lasting victories in politics, there is only the remorseless grinding forward of events. … Perhaps Caesar is right - this whole republic needs to be pulled down and built again.”

Publisher, Blue Ear Books